For decades, cholesterol has been misunderstood. We’ve been told to fear butter, eggs, and red meat—foods that traditional cultures have thrived on for generations. Yet modern research reveals a far more nuanced story about cholesterol, heart disease, and dietary fat. In this article, I’ll break down the difference between LDL and HDL cholesterol, how cholesterol truly impacts heart health, and which dietary and lifestyle choices support a resilient cardiovascular system. We’ll also explore the crucial distinction between dietary cholesterol and blood cholesterol, and why mainstream messaging on the topic has steered us in the wrong direction.

We’ve been led to believe that lowering cholesterol, particularly LDL (low-density lipoprotein), is the key to preventing heart attacks and strokes. What if the real issue isn’t cholesterol itself, but rather inflammation, oxidation, and metabolic dysfunction? The truth is, cholesterol plays a vital role in the body, and instead of fearing it, we need to understand how LDL and HDL function and what really drives cardiovascular disease.

What Is Cholesterol and Why Do We Need It?

Cholesterol is an essential substance found in every cell of the body. It plays a critical role in:

- Building cell membranes – Every cell in the body relies on cholesterol for structural integrity.

- Producing hormones – Cholesterol is the precursor for hormones like testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol.

- Making vitamin D – Sun exposure helps convert cholesterol in the skin into vitamin D.

- Creating bile acids – The body needs cholesterol to produce bile, which helps digest fats.

Without cholesterol, the body wouldn’t function properly. The issue isn’t cholesterol itself—it’s how it interacts with inflammation and oxidative stress.

Rethinking Cholesterol: Dietary Myths vs. Biological Reality

For decades, we were told that eating high-cholesterol foods like eggs, butter, and liver would clog our arteries and cause heart disease. This fear sparked the low-fat food craze of the late 20th century, encouraged by guidelines that treated all cholesterol as a threat. But newer science—and a look back at how our ancestors ate—tells a very different story.

Cholesterol is not inherently harmful. In fact, it’s essential. Your body produces about 75–85% of its cholesterol in the liver and intestines, using it to make hormones (like estrogen and testosterone), build cell membranes, synthesize vitamin D, and form bile for digestion. The remaining cholesterol comes from food, but for most people, this dietary cholesterol has minimal impact on blood levels.

Dietary cholesterol refers to the cholesterol found naturally in animal-based foods like eggs, liver, and butter. Once eaten, it’s absorbed through the intestines and packaged into lipoproteins called chylomicrons, which enter the bloodstream and eventually contribute to the body’s cholesterol pool. From there, it may be repurposed or routed through LDL and HDL as needed.

A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition examined the effects of dietary cholesterol on cardiovascular disease risk in healthy adults. The study concluded that “dietary cholesterol did not statistically significantly change serum triglycerides or very-low-density lipoprotein concentrations.” In other words, eating cholesterol-rich foods—like eggs, butter, or shellfish—had little measurable impact on the blood fats most associated with heart disease.

So where did the confusion start? Early studies linked high-cholesterol foods to heart disease, but they failed to isolate other variables like refined carbohydrates, trans fats, smoking, and chronic inflammation. These flawed correlations were generalized into sweeping dietary advice. More recent, well-controlled research has dismantled those assumptions. For example, the famous Framingham Heart Study—once used to support the cholesterol-heart disease link—later found no connection between dietary cholesterol and blood cholesterol levels in most people.

Even more telling is the example of traditional, non-industrialized societies. Dr. Weston A. Price documented numerous Indigenous communities across the globe—many consuming large amounts of saturated fat, organ meats, and raw dairy—with virtually no heart disease, tooth decay, or obesity. These nutrient-dense, ancestral diets were rich in cholesterol but paired with low levels of sugar, no seed oils, and active lifestyles.

Today, we know the real issue isn’t cholesterol itself, but how the body processes it—something driven more by metabolic health, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation than by whether you ate four eggs for breakfast. Understanding the difference between dietary cholesterol and blood cholesterol is the first step in unraveling what really matters when it comes to heart health.

What Are LDL and HDL, Really?

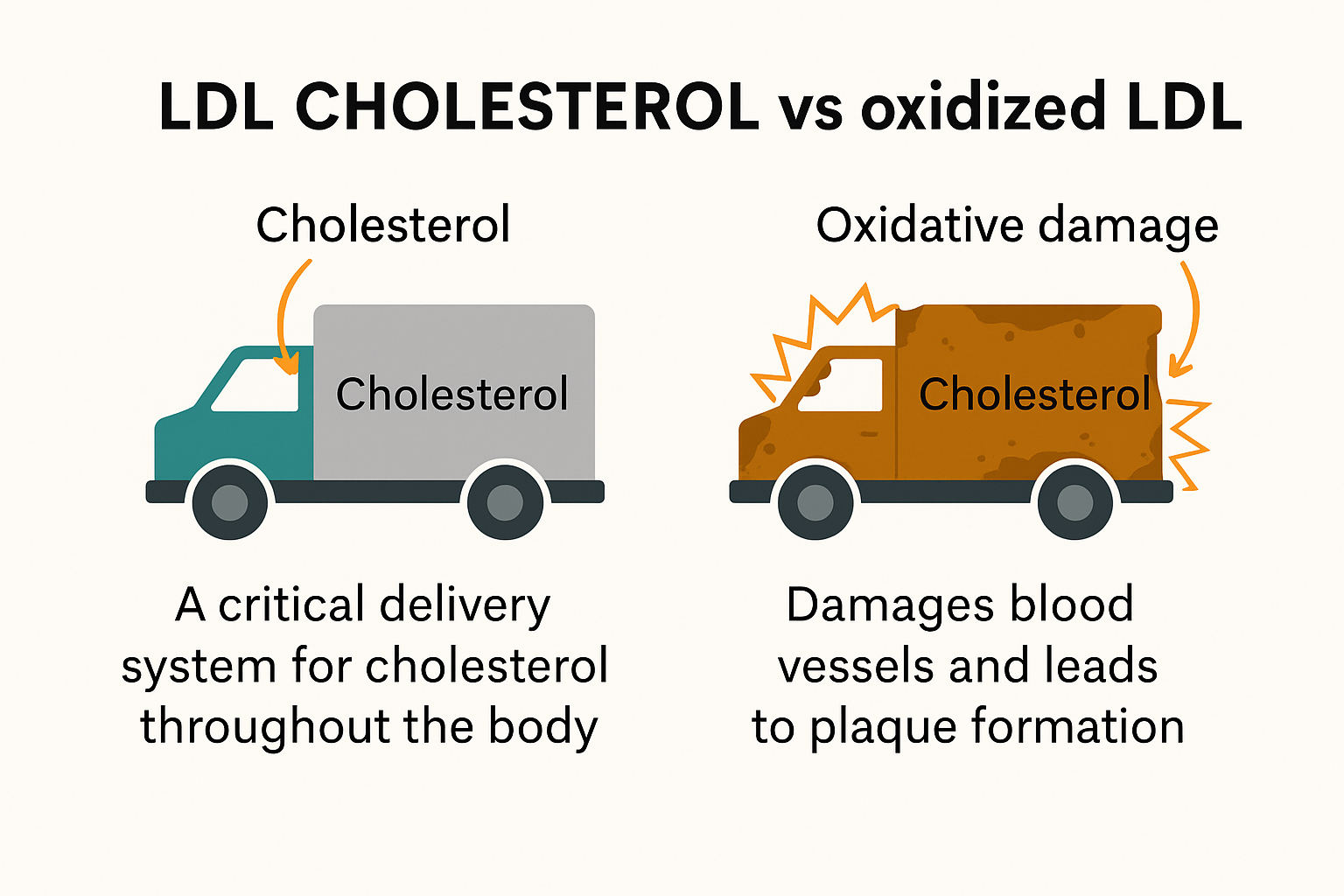

Cholesterol itself doesn’t float freely in your bloodstream. It has to be carried by special particles called lipoproteins—and that’s where LDL and HDL come in. These two types of lipoproteins have very different jobs, but they’re both essential for keeping your body functioning properly.

LDL (low-density lipoprotein) is produced by the liver as part of a larger particle called VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein), which transports triglycerides to your tissues. As these triglycerides are offloaded, VLDL transforms into LDL, which then delivers cholesterol to cells throughout the body. This cholesterol is used for vital tasks like building cell membranes, producing hormones, and repairing tissues.

HDL (high-density lipoprotein), on the other hand, is also made by the liver and intestines, but with a different mission. HDL acts like a cleanup crew—it starts off as a small, empty protein shell and circulates through your bloodstream to collect excess cholesterol from cells and other lipoproteins. It then returns that cholesterol to the liver for recycling or elimination in a process known as reverse cholesterol transport.

So while LDL and HDL are often called “types of cholesterol,” they are not cholesterol themselves. They are lipoproteins—complex particles made of fat (lipid) and protein—that carry cholesterol through the bloodstream. Cholesterol is a single waxy molecule, while HDL and LDL are more like vehicles or delivery trucks that transport it (along with triglycerides, phospholipids, and fat-soluble vitamins).

It’s also worth noting that cholesterol exists in two general forms in the body:

- As part of lipoprotein particles like LDL and HDL (circulating in the blood), and

- As free or unbound cholesterol embedded in cell membranes and tissues throughout the body.

Understanding how each functions is key to unraveling the real story behind heart health and the role cholesterol plays in it.

LDL Cholesterol: The “Bad” Misconception

LDL, or low-density lipoprotein, is often labeled as “bad cholesterol” because it transports cholesterol from the liver to cells. When LDL levels are high, mainstream medicine assumes that it increases the risk of plaque buildup in arteries. However, this assumption is overly simplistic. In fact, LDL is crucial for brain function and physical recovery.

🧠 LDL and Brain Function

- Your brain is made up of nearly 60% fat, and cholesterol is essential for building brain cells, myelin sheaths (which insulate nerves), and synapses (where neurons communicate).

- LDL delivers cholesterol to brain cells, where it’s used to make neurotransmitters, maintain cellular integrity, and support cognitive function.

- While the brain makes much of its own cholesterol, it still depends on systemic LDL to support repair and signaling pathways—especially during times of stress or injury.

🛠️ LDL and Tissue Repair

- LDL also transports cholesterol to damaged tissues to support cell membrane repair, wound healing, and hormone production (especially cortisol, testosterone, and estrogen).

- After physical stress, injury, or surgery, your body relies on LDL to deliver the raw materials needed to rebuild and regenerate.

When LDL Becomes a Problem: The Role of Oxidation

LDL on its own is not harmful—it’s doing its job, delivering cholesterol to cells that need it. But problems arise when LDL particles become oxidized.

Oxidation happens when LDL particles are exposed to free radicals, toxins, or chronic inflammation—factors that can damage the LDL structure. Once oxidized, these LDL particles are no longer recognized as useful by the body. Instead, the immune system sees them as threats.

In response, immune cells (especially macrophages) rush in to engulf the damaged LDL, forming what are known as foam cells. These foam cells accumulate within the artery walls and form the beginnings of atherosclerotic plaque. Over time, this buildup narrows the arteries, restricts blood flow, and increases the risk of heart attack and stroke.

It’s important to understand that it’s not simply “high LDL” that creates risk—it’s oxidized LDL in the presence of systemic inflammation that drives the progression of heart disease. This is why lifestyle factors like a nutrient-dense diet, managing blood sugar, and reducing exposure to oxidative stress are so critical to long-term cardiovascular health.

Think of LDL as the delivery truck, HDL is the cleanup crew, and oxidized LDL is a flaming delivery truck that crashed into a school.

LDL is the delivery truck, bringing cholesterol to cells that need it for repairs, hormones, and energy. HDL is the cleanup crew, collecting leftover cholesterol and bringing it back to the liver for recycling. But when inflammation or oxidative stress is high, LDL turns into a flaming delivery truck that crashes into the arterial wall—that’s oxidized LDL. The immune system panics, rushes in to clean up the damage, and accidentally creates a traffic jam of foam cells and plaque. Meanwhile, HDL shows up with a fire extinguisher and broom, trying to clear the scene.

Factors That Cause LDL to Become Harmful

- Chronic inflammation – Systemic inflammation damages the endothelial lining of blood vessels, making it easier for oxidized LDL to accumulate.

- High blood sugar and insulin resistance – Excess glucose, often as the result of chronic stress, in the blood leads to glycation, making LDL particles more prone to oxidation.

- Industrial seed oils – Oils like soybean, corn, and canola promote oxidative stress and inflammation, damaging LDL particles.

- Poor liver function – Since the liver regulates cholesterol levels, a sluggish liver can contribute to imbalances in LDL and HDL.

HDL Cholesterol: The Protective Factor

HDL, or high-density lipoprotein, is known as “good cholesterol” because it helps remove excess cholesterol from the bloodstream and transports it back to the liver for processing. High HDL levels are associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease because HDL:

- Clears cholesterol from arteries – Reducing plaque formation and promoting vascular health.

- Has antioxidant properties – Protecting LDL from oxidation.

- Supports immune function – Contributing to overall cardiovascular resilience.

HDL cholesterol is produced primarily by the liver and small intestine. It isn’t found directly in food—unlike dietary cholesterol—but is instead manufactured by your body in response to healthy metabolic activity. HDL acts as a “scavenger,” traveling through the bloodstream to collect excess cholesterol from tissues and other lipoproteins and returning it to the liver for processing or elimination. Nutrient-dense foods—especially those rich in omega-3s, healthy fats, and antioxidants—help support HDL production and function.

However, recent research has shown that simply having high HDL levels doesn’t automatically translate to better heart health. What matters more is how well HDL functions—specifically, its ability to collect and return excess cholesterol, reduce inflammation, and protect against oxidation. In fact, some people with high HDL may still be at risk if their HDL particles are dysfunctional or overwhelmed by chronic inflammation.

This means that HDL’s quality—its efficiency, structure, and antioxidant activity—may be more important than its quantity on a lab report. Lifestyle factors like nutrition, metabolic health, and toxin exposure can all influence HDL’s function. A truly protective HDL profile depends on more than just a high number—it depends on a body that’s operating in balance.

HDL is most positively influenced by overall metabolic health, not just one superfood—so pairing nutrient-dense foods with regular movement, sunlight, and low sugar intake is key. Here are some real-food examples that support HDL production and function:

🥑 Healthy Fats

- Avocados – rich in monounsaturated fats and fiber

- Extra virgin olive oil – antioxidant-rich and anti-inflammatory

- Raw nuts & seeds – especially almonds, walnuts, chia, and flax

- Coconut oil (in moderation) – may help improve HDL in some people

🐟 Omega-3-Rich Foods

- Wild-caught fatty fish – salmon, sardines, mackerel, anchovies

- Pastured eggs – especially from chickens raised on greens and bugs

- Grass-finished meats – higher in anti-inflammatory omega-3s

- Cod liver oil – traditional source of DHA/EPA and fat-soluble vitamins

🌿 Antioxidant-Rich Whole Foods

- Berries – support HDL function by reducing oxidative stress

- Dark leafy greens – provide folate and magnesium, important for lipid metabolism

- Garlic – shown in some studies to modestly improve HDL

🧈 Traditional Animal Fats (in balance)

- Grass-fed butter or ghee – rich in CLA and fat-soluble vitamins

- Pastured lard or tallow – used ancestrally and may support healthy cholesterol profiles when part of a whole-food diet

The Real Issue: Cholesterol Ratios and Inflammation

Instead of focusing solely on total cholesterol, a better predictor of heart health is the ratio between LDL and HDL, along with markers of inflammation.

- LDL to HDL ratio – A healthy ratio is generally 3:1 or lower.

- Triglycerides to HDL ratio – A ratio below 2:1 is ideal for metabolic health.

- C-reactive protein (CRP) – A key marker of inflammation that can indicate heart disease risk more accurately than cholesterol levels alone.

How to Optimize Cholesterol for Heart Health

Rather than focusing on lowering LDL with statins, a better approach is to support cholesterol balance naturally by reducing inflammation, preventing oxidation, and improving metabolic function. For a deeper look at the risks of statins and alternative heart health strategies, see this article on the cholesterol myth.

1. Reduce Inflammation

- Avoid industrial seed oils – Replace canola, soybean, and corn oil with grass-fed butter, tallow, coconut oil, and extra virgin olive oil.

- Manage blood sugar – High blood sugar contributes to LDL oxidation and arterial damage.

- Prioritize nutrient-dense foods – Foods rich in antioxidants, like berries, dark leafy greens, and turmeric, help combat oxidative stress.

2. Support Healthy Cholesterol Transport

- Eat more omega-3s – Wild-caught fish, grass-fed beef, and pastured eggs help improve cholesterol balance.

- Consume vitamin K2 – Found in grass-fed dairy, natto, and pastured eggs, K2 helps direct calcium away from arteries and into bones.

- Exercise regularly – Movement increases HDL levels and improves circulation.

3. Address Stress and Sleep

- Practice breathwork – Techniques like 4-7-8 breathing and box breathing help reduce cortisol and inflammation. For more on stress management, check out this guide to holistic heart health.

- Get morning sunlight – Natural light exposure helps regulate circadian rhythms, balancing cholesterol and hormone levels.

- Try cold plunges – Cold therapy stimulates circulation and helps improve heart rate variability.

4. Improve Liver Function

- Eat bitter foods – Foods like dandelion greens and milk thistle support liver detoxification.

- Stay hydrated – Proper hydration supports bile production and cholesterol metabolism.

Final Thoughts

LDL and HDL cholesterol are not the enemy—oxidation, inflammation, and poor metabolic health are the real drivers of heart disease. Instead of relying on statins to artificially lower cholesterol, focus on reducing inflammation, balancing cholesterol ratios, and improving overall heart function. For more strategies, check out this article on inflammation and heart disease.

Looking for more natural ways to improve heart health? Learn how balancing omega-6 and omega-3 plays a role in cardiovascular wellness, or explore how to clear arteries naturally.